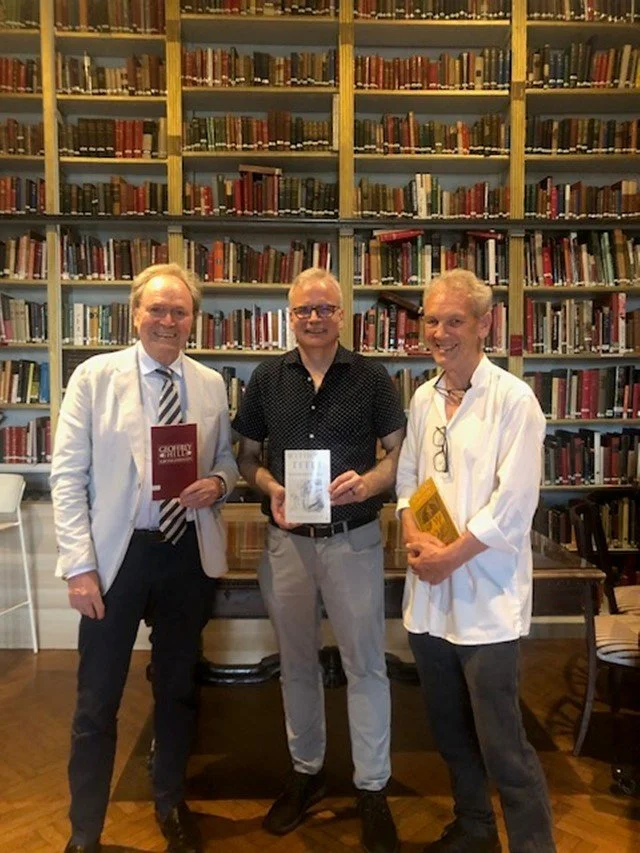

Making Music | Leonard Sanderman

Photo by Simon Godsave

Keble Choir member Ellen Roxby (2023 Theology and Religion) interviews former Organ Scholar Leonard Sanderman (2010 Music) about his memories of Keble and his current work reviving the chorister tradition in Horbury, West Yorkshire.

Please could you describe your recent work in music?

Over the past year I’ve set up three new children’s choirs in Horbury, a village on the south side of Wakefield which includes areas of significant social and economic deprivation.

The earliest evidence of a surpliced choir in Horbury goes back to 1843. Canon Sharp had just returned from his studies at Oxford, heavily influenced by John Keble and his fellow Tractarians, and turned these teachings into practice in Horbury, making it one of the very first churches in the English Choral Revival. Despite these old roots, you would have found no choirs in these churches if you’d come to a service ten years ago.

Last year, the Vicar and I kicked off a Choral Development Programme, working closely with primary schools, and we now have 26 choristers singing across four services of Evensong each week. It’s remarkable how quickly they’ve grown in confidence and musicianship since we began last autumn. Watching them discover a love of music – and a sense of belonging – has been one of the most rewarding things I’ve ever done.

What inspired you to come to Keble?

I was born in Rijssen, in the Netherlands, in 1991. My school had no music curriculum whatsoever. However, my dad is a wonderful musician and composer, and taught me everything he knew. When I came to Oxford for organ scholarship auditions in 2008, Keble was my first choice, and to this day I am so grateful that the Director of Music, Simon, gave me the opportunity to become the first person from my school to go to Oxford.

He encouraged me to take a gap year to get to know English choral tradition a bit better, which I spent working at Cheltenham College, after which I was organ scholar at Keble from 2010-2013.

How did your involvement with Keble choir impact your experience of Oxford?

Now that I’m a professor, I can safely admit that, academically, I was not always the most disciplined undergraduate. For most of second year, my routine was to do Wednesday Evensong, then Hall, and then pop to the bar until midnight. As long as I then got up for 3am, I could get the essays done for my 9am and 11.30am tutorials. I’m quite sure my tutors spent more than a few hours wondering what on earth to do with me.

When it came to Chapel, the expectations were very different. Choir gave me structure, purpose, and a place to channel my energy. The atmosphere was demanding yet joyful. There was a real sense that what we were creating together was meaningful. The standards were very high, but there was also space for humanity. If Simon knew that I’d spent ages learning a piece, and I made a mistake in the service, there wouldn’t be the death-stare you’d get from many conductors. Instead you’d see an encouraging smile and a gleeful wink. I try to model this with my students and singers now.

Do you have a standout memory from your time in Chapel?

One of my favourite memories was one involving Simon Cuff who was an ordinand at the time. There had been some work done in chapel, and as a result, it reeked of something – I forget if it was turpentine or paint. Either way, he decided the best way to deal with this was to close the Chapel doors, charge a thurible, and smoke the place out to a point where the only thing you could smell was the fragrance of incense. At this point, I came in to do some practice. There he was, in the middle of chapel, unable to see more than a few metres in any direction due to the smoke, when suddenly the large West Doors opened, and in the beams of sunshine piercing the smoke, just a single man, in a bright white suit. Simon swears to this day that for a split second he thought the good Lord had chosen Keble Chapel as venue for the Second Coming. Sadly, it was only me, although I do maintain that I did look divine in that suit.

How would you describe your trajectory from your time at Keble to your current work?

After Keble, I became organ scholar at Chichester Cathedral. I was quite lonely, and after the warm atmosphere of Keble Choir, the relentless way the kids were pushed here didn’t quite sit right with me. Deciding to leave the Cathedral sector, I moved to Yorkshire, and undertook an MA in English Church Music at York. My supervisor encouraged me to stay on for a PhD exploring Anglo-Catholic liturgical music, which began, quite fittingly, with a chapter on the poetry of John Keble’s The Christian Year.

I now combine a number of roles: I am a visiting lecturer at the University of York; Associate Professor at Leeds Conservatoire; Director of Music at Horbury with Horbury Bridge; and in recent years I’ve been building up a portfolio of projects as an Organ Advisor.

What did you learn at Keble that you still carry with you today?

I am so grateful for the opportunity Keble gave me. That opportunity was transformative. A door was opened for me, and it changed everything. That’s what drives my work today: I want young people, with all sorts of backgrounds and starting points, to encounter the same sense of possibility.

It also taught me that excellence and kindness aren’t mutually exclusive. The very best music-making comes from people who demand high standards but genuinely care about one another.

What are some of the biggest rewards and challenges of your work now?

The children are by far the biggest reward. Their enthusiasm, capacity for growth and pride for success is something you can feel in the room, and it fires them up. It’s so fulfilling.

The challenges are also very real. Fundraising to square the budget every year is consuming, and the sheer intensity of building something sustainable from scratch is as exhausting as it is exhilarating. This sort of work requires commitment, and a solid, stable grounding. If you’re not prepared to give it a decade or more, the work will suffer.

Where is the greatest opportunity for impact today?

The most meaningful musical work is often done in the margins, after school, in a village hall, in a church vestry, with three children and a keyboard that only works if you keep pushing in the power lead and switches off if you so much as look at Middle G. The wonderful music we hear from our College and Cathedral Choirs at Christmas does not exist without those beginnings.

Look to the places where music provision has been cut back or never existed. Many of John Keble’s students went out to become vicars of the poorest parishes across the country. Around this part of West Yorkshire, it’s still known as ‘coalface mission’. A single committed musician in a place like this can alter the trajectory of hundreds of young lives. And a place like Keble can then build them up further, to do the same all over again.

What advice would you give to someone interested in music education or community work?

Building up this sort of musical life only works through trust, and that takes time. Just keep showing up. Just keep at it. Get stuck in. In one of our partner schools, the staff invited me to play in their annual rounders game between staff and leavers. Our chorister intake doubled there, the next year. Nothing builds trust like the willingness to go flat on your face a few times while trying to outrun a ten-year-old.

Be kind, be humble, and listen.

Final thoughts?

As Christmas approaches, life is full of music. For most of the children in Horbury, this Christmas will be the first time they’ve ever sung in a Carol Service. It’ll be the first time in decades that a lone chorister processes to the stalls by candlelight, singing ‘Once in Royal David’s City.’ It’ll be the first time their parents and carers will shed a quiet tear of pride during the quiet verse of their favourite carol. But it certainly won’t be the last time. Next year, it’ll probably still be here. But in ten years, it might be in Keble Chapel, and in twenty years..?

So wherever you are this Christmas, whatever wonderful music you’re drinking in or sharing out, think also a little of the children in Horbury singing their first Carol Service: wide-eyed, unsteady, and utterly magnificent. It’s not about the destination – it’s about creating the opportunities that give them the chance to step into a life of stories, songs, and friendships.

That, to me, is Keble at its best: a place of opportunity. Where failure is met with that cheeky, encouraging smile, and where the possibility of the outstanding becomes an open door.

Photo by Beatrix Calow